PRINTMAKING.

print studio, Canterbury University Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha

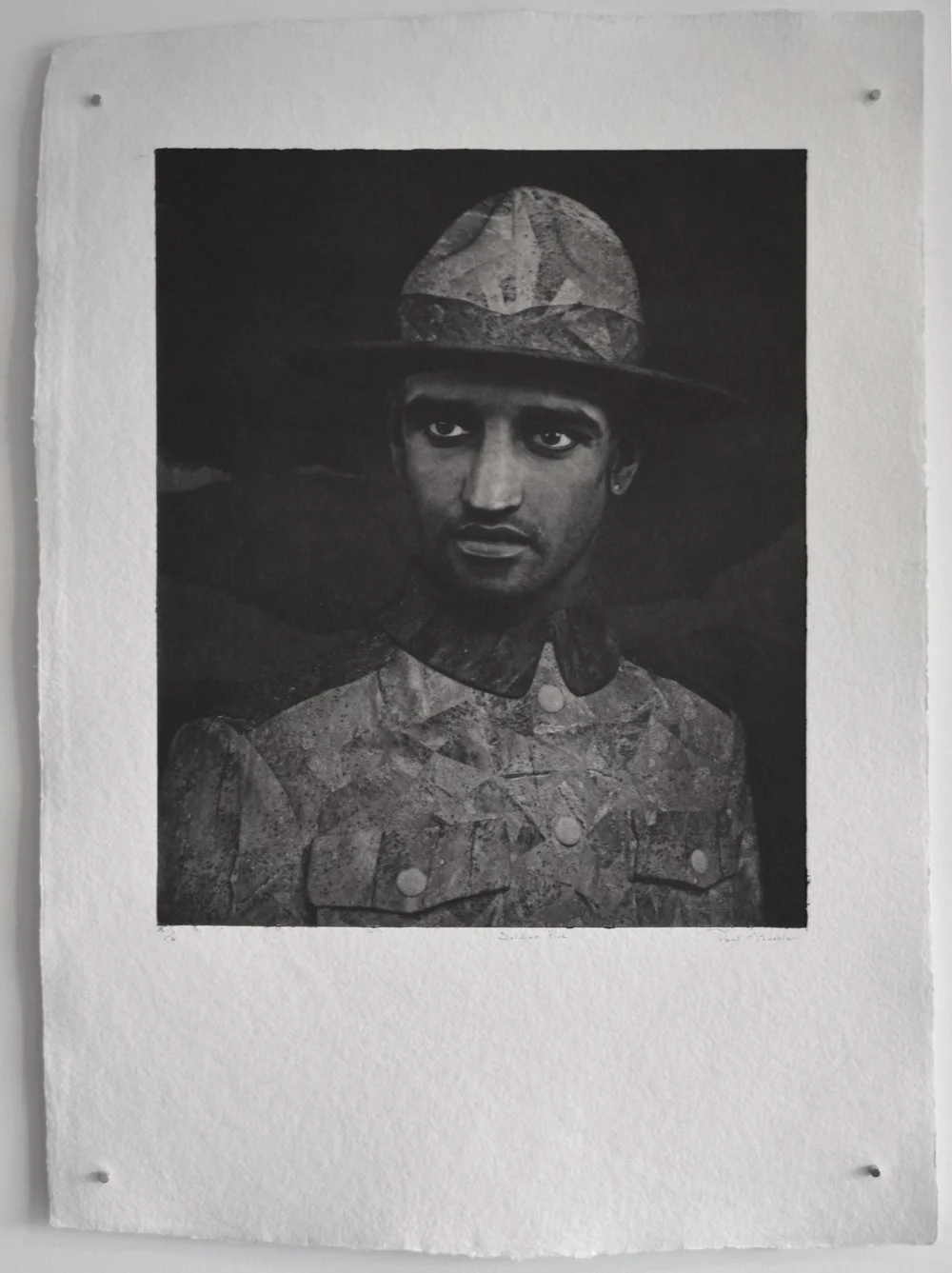

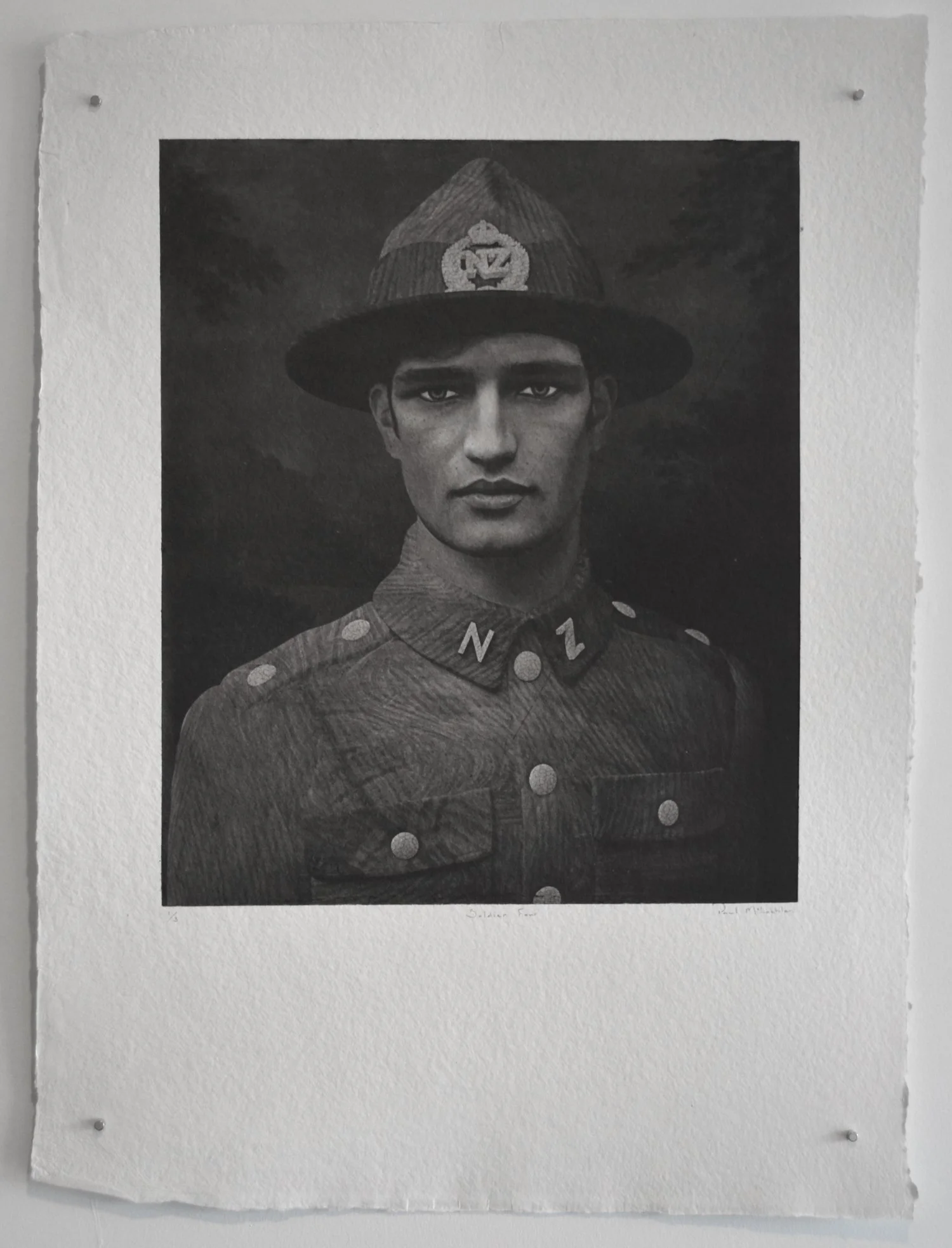

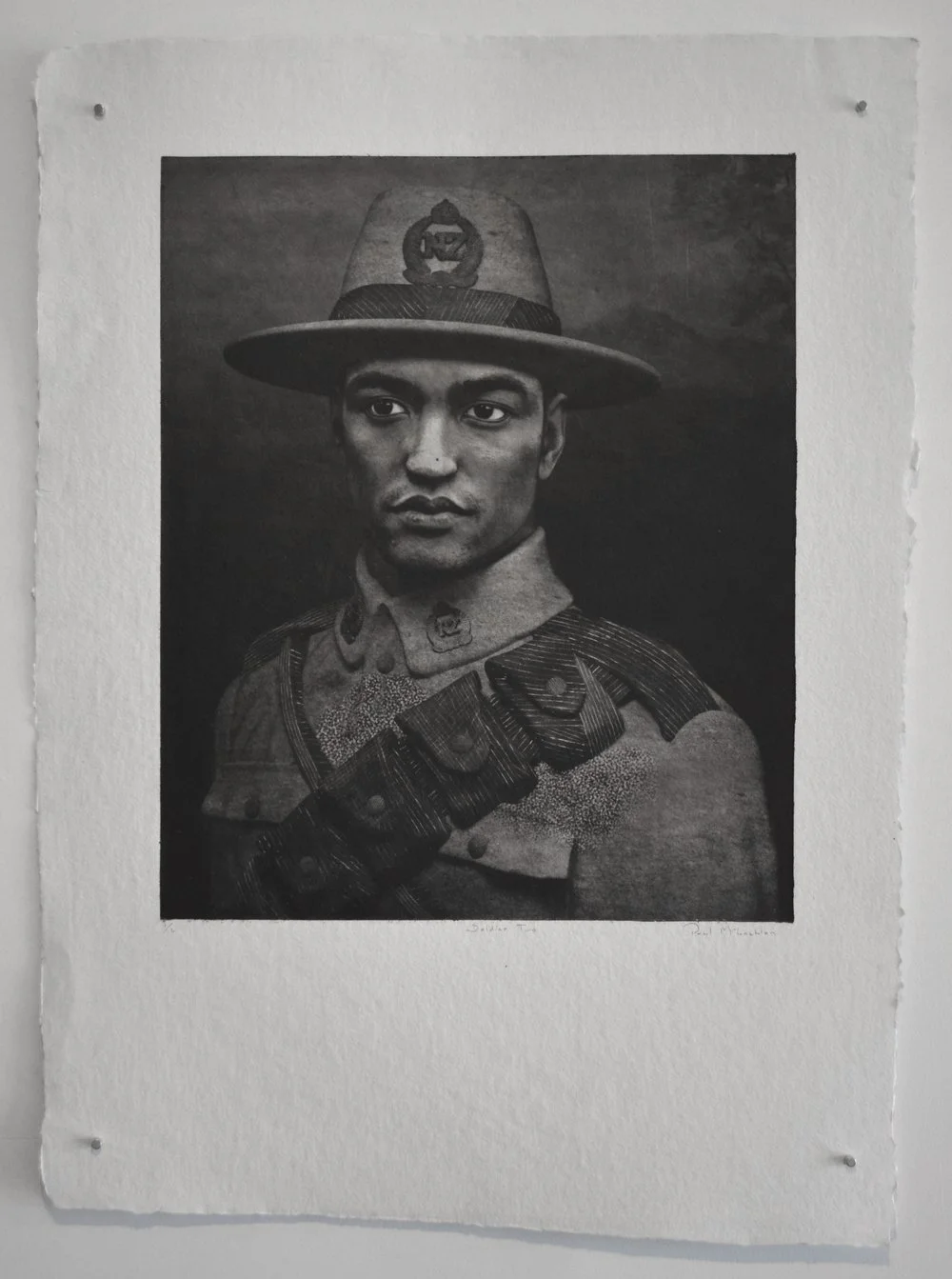

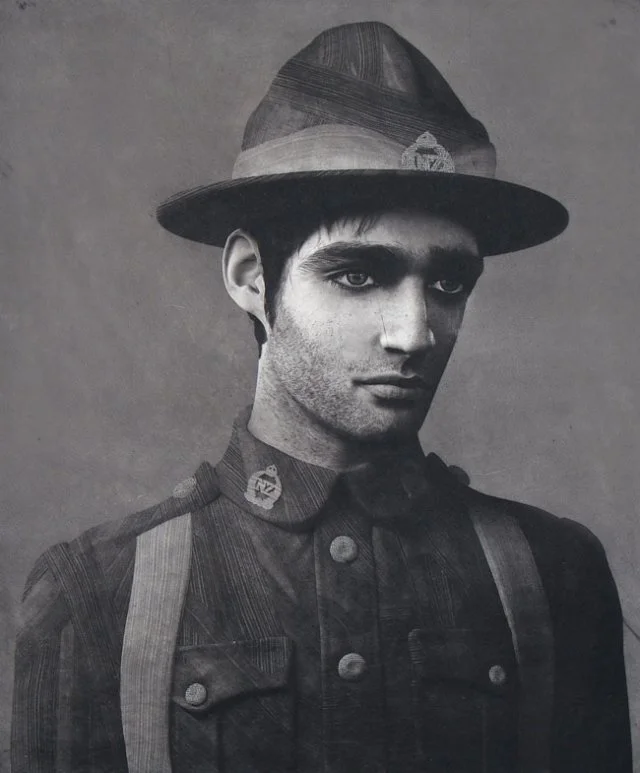

PRINTS OF WW1 SOLDIERS

Andrew Paul Wood – 28 July, 2013

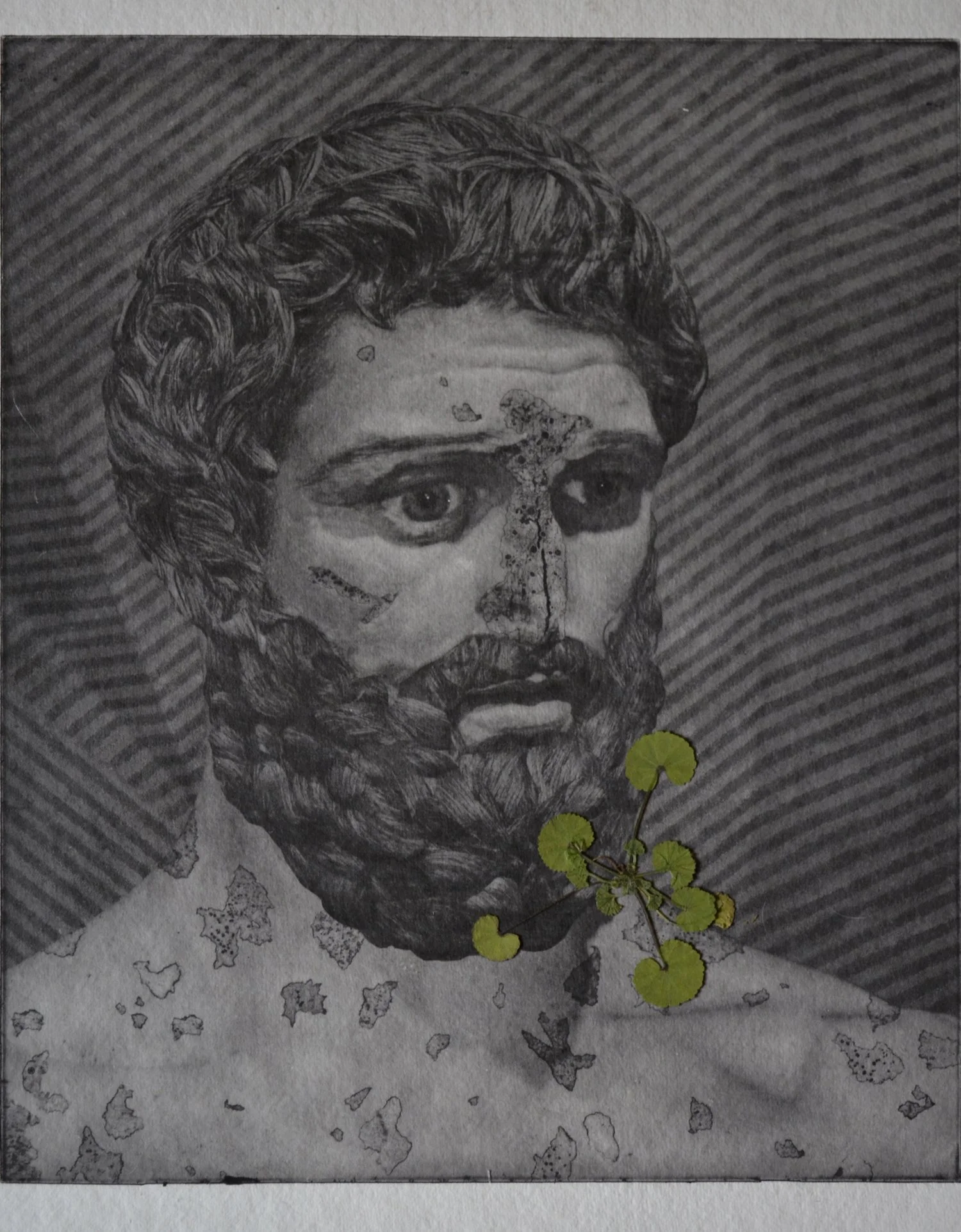

Next year July 28 marks the centennial anniversary of the First World War, a conflict that in many ways marks the emergence of New Zealand onto the world stage as a modern nation, tainted with the loss of 1.64 percent of New Zealand’s population. Every school, society and club of the time had its misericord. Every town in Aotearoa, no matter how small, has its own war memorial, and it is these that provide the source material for Paul McLachlan’s suite of photographic prints Home Ground at Chambers 241 gallery.McLachlan is a New Zealand printmaker with a BFA (hons) from Massey, Wellington (2008). In 2010 he received the select award, and his work placed in the University of Canterbury’s collection. In 2013, McLachlan received the Susan Ethel Jones Fine Arts Travelling Scholarship to take up an artist residency at the Large Format Printmaking Studio in Venice.The thick-edged black and white photo-intaglio prints record the faces of the ten South Island marble statues of the thirty-eight soldiers standing to attention, carved in Carrara, Italy and erected around New Zealand to commemorate the Great War. Some of the statues were given their likeness from photographs of particular New Zealand soldiers, thus closing the circle with these works. Using digital sculpting software McLachlan has digitally remodelled and humanised into pseudo/hyper-realistic versions - a Pygmalion metamorphosis accomplished digitally. Like some forensic process, the sculpture beneath is layered with skin and hair textures, and even a suggestion of the lichen encrusting the originals and pitted marble, giving them the aura of life or even something more idealised and larger than life - simultaneously an inversion and mannerist intensification of the Baudrillardian simulacrum.On the other hand it is ultimately a deception: something that always was frozen, a still life, is given the illusion of having been frozen by the photographic moment. There is, perhaps, a Freudian homage to and erasure of an art-historical forebear with covering over the impassive gaze into the distance, a tradition in warrior portraiture that can be traced back to Lysippos’ sculptures of Alexander the Great. Perhaps we may interpolate a similar function as Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History”:“His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet. He would like to pause for a moment so fair, to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm.” (Benjamin, On the Concept of History IX, trans. Dennis Redmond 2005)Comparisons can be made with the composite photographs created by Ludwig Wittgenstein to illustrate his theory of rhizomatic “family resemblances” and eugenicist Francis Galton’s composite photographs meant to test his phrenological and physiognomic theories. Anonymous templates are transformed into human individuals that can be identified and empathised with, and further serve to bring to life and immediacy a part of our national history most of us only think about once a year on ANZAC Day.The effect is intensely powerful and richly atmospheric. Despite their pastiche and fictionality, the images hint at an interior life, even if the eyes all too often seem dead and mineral. But then again, the allusion to the nullity of photographic death and preservation seems a logical one for a war memorial to the dead. The relative blandness of the expressions allows the viewer to project their own readings onto each character. It becomes, in effect, a kind of prosopopeia - a voice that addresses us from beyond the grave. It is a unique synthesis and really quite an extraordinary achievement. McLachlan’s attention to detail and his printmaker’s skill are everywhere evident. This is an astonishing tour de force.

soldier five photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier four photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier nine photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier three photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier ten photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier two photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier eight photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier one photo-intaglio print 2013

soldier six photo-intaglio print 2013

home ground pataka art museum, porirua

(Un)common ground

ilam gallery

2011

21 - 24 June 2011

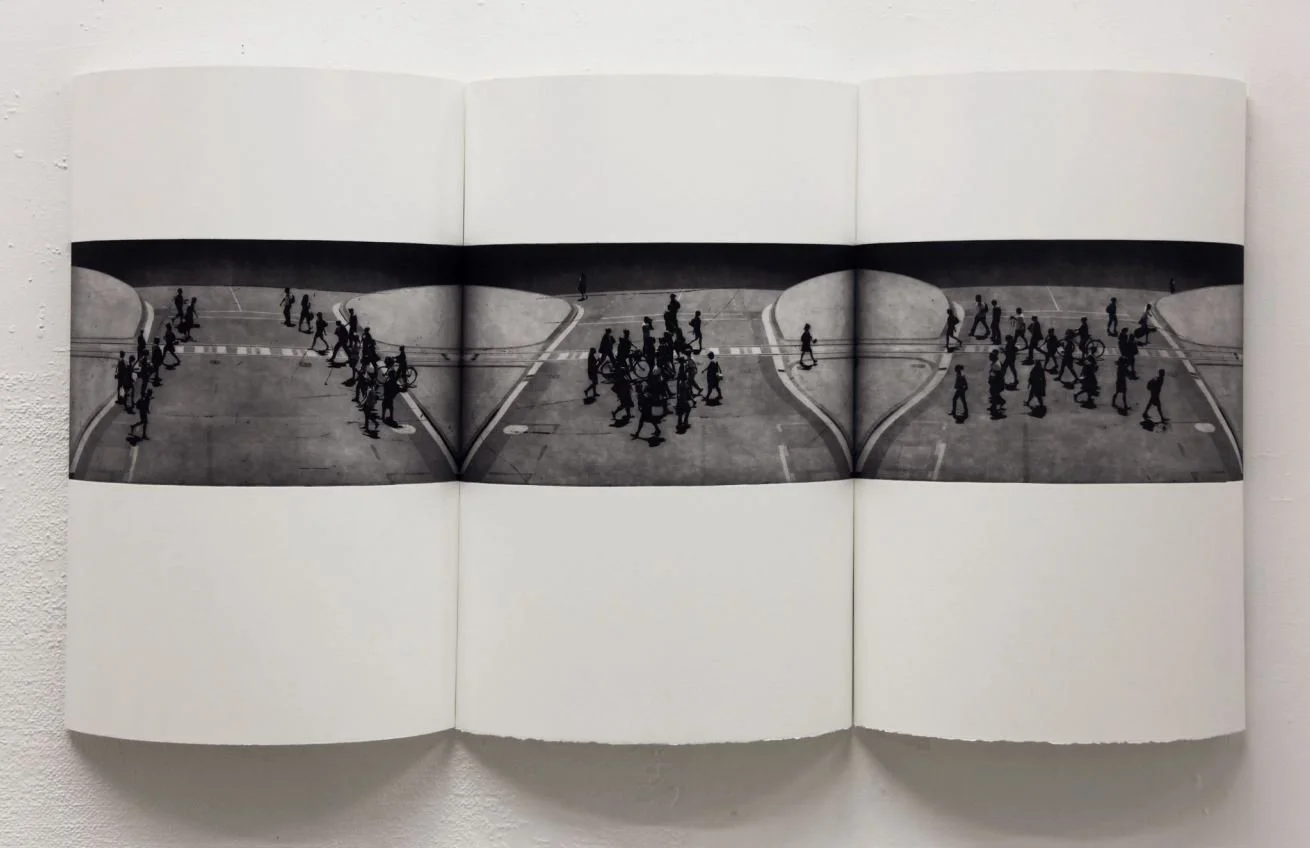

The photo-intaglio prints that make up (Un) Common Ground might initially appear as simply familiar territory to the art of printmaking, retaining all the obsessive attention to making that usually characterise it as a serious art practice. Paul McLachlan is a meticulous and fussy practitioner, yet there is more than just method going on in (Un) Common Ground to complement and transcend the artist’s attention to process and detail.As black-and-white sequential images of figures viewed from afar, moving through the inner city of Christchurch pre-22 February, these prints invite - even encourage - an inherent voyeuristic pleasure. All the figures in the 12 prints in (Un) Common Ground are placed in a middle distance that separates them in space, just far enough away from the camera to allow them to be spied upon. They become anonymous as individuals and can be viewed with detachment and a degree of secrecy, yet equally, they are still close enough to scrutinise their behaviours. Comparisons between the viewer’s act of looking, James Stewart and Rear Window, or for that matter, any Hitchcock movie from the 1930s (Sabotage comes to mind, especially the crowd scenes), are entirely appropriate. On one level, (Un) Common Ground is constructed on the premise of Hitchcock’s cinematic voyeurism: the fake, grainy black-and-whiteness of McLachlan’s images, the sequential silent movie references and the detached distance between viewer and protagonist. The exhibition’s title is just as complicit in this plot. In some works, for example, the etched ground behind the figures isolates them from reality and a familiar experience of the world. They become - uncommon - and acceptable as subjects for our observation.McLachlan also turns the viewer’s guilty pleasure in the act of watching, back on them with the majority of works consisting of three to four curved sequential images that forces the gallery visitor to track their gaze around each image, becoming directly involved in the work itself. McLachlan’s treatment of the print insists that they move forward from image to image with each step revealing more about the scene and its players, while obscuring moments already seen. In The Crossing, a figure walking two dogs enters from top left to middle and exits in the third image, behind his canine companions. It’s a physical journey through time and space for the figures and the viewer, as well as an orchestrated formalist study in space and tonality.However, the best of McLachlan’s work is more than formalist, nostalgic, clever or merely skilful, rather, prints such as Kapa Haka, are genuinely sentimental and touching images, rendering private moments between public performances, with figures caught and suspended, prior to a return to life on stage. It’s an Edward Hopper moment with all the accompanying reflection and melancholy that the America realist was similarly capable of conjuring up.Indeed, the emotional potency of McLachlan’s prints is the strength of (Un) Common Ground. The only reservation lies in works such as The Procession where the curved prints in relief from the gallery wall are visually linked as a unified series of symmetrical images. The Procession seems somewhat self-conscious and notice-me clever, highlighting the challenges McLachlan faces. How much longevity does the unframed curved sequential print as artist’s trademark retain? How long can it be sustained before it descends to formula? Fortunately, it’s a challenge that McLachlan as printmaker seems more than ready for.Warren Fenney

intersect, Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

seep (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

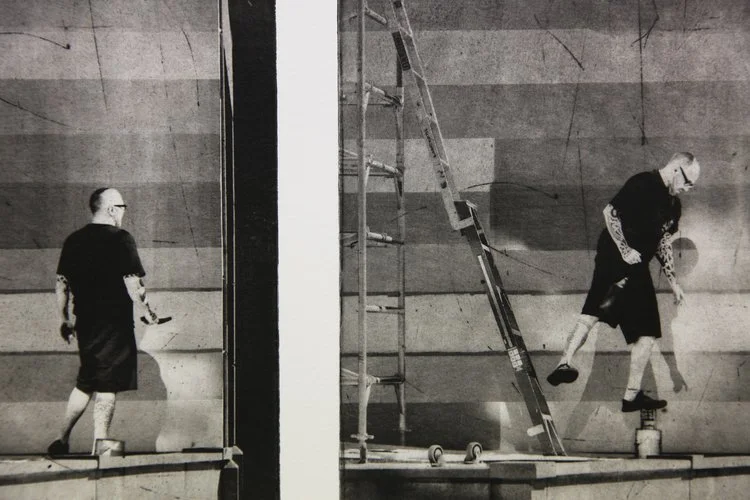

mural with wayne youle (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 1000 x 700mm, Images: 210 x 210mm

procession (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

(Fold) unfold (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

(Fold) unfold (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

The Siege (detail), Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 180 x 415mm

the crossing (detail) Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 200 x 415mm

bench boy (detail) Photo-intaglio, print Paper: 700 x 100mm, Images: 195 x 195mm

hapa haka Photo-intaglio print, Paper: 500 x 700mm, Images: 200 x 415mm

playwright

Photo-intaglio print

Paper: 1000 x 700mm, Images: 800x500mm

Finalist in the New Zealand Contemporary ARt Awards 2014